Australian supporters can sit back, relax and take a breath. The pain is over. When all is said and done, two teams from New Zealand – the Blues and Highlanders – will be contesting the first-ever Super Rugby Trans-Tasman final.

The Kiwi sides have dominated the tournament, winning 23 out of 25 matches, and they have offered the Super Rugby AU competition a very dry dose of perspective in the process.

They have held sway in most of the critical areas in the modern game: at the transitional phases in attack and counter-attack, and through their ability to cut corners in all of the contact situations. It has been an education.

The coaching staffs at the other four Australian franchises might want to pause for a moment, and wonder just why it is that the Western Force have enjoyed the most consistent record against New Zealand opposition over the course of the five matches.

Although the Force didn’t win a game, they did at least manage to participate fully in some tight contests, conceding the fewest points of an Australian team (148) and the lowest average points differential: -13 per game, compared to -14 by the Brumbies, -17 by the Reds, -24 by the Rebels and -28 by the hapless Waratahs.

Tim Sampson and co. identified the areas of real need against New Zealand opposition. They had the highest tackling success percentage, at 86: four per cent higher than the next best (the Brumbies) and a massive ten per cent better than the cellar-dwellers, the Reds and Rebels.

In the final round against the Blues, their second-half comeback was triggered by neutralising one of the great strong points in the New Zealand game: the ability to win blue riband ball from the tail of the lineout.

During Trans-Tasman, New Zealand sides threw the ball to the back of the lineout five per cent more than Australian teams (31% to 26%). They were also more successful at winning possession in that area, retaining 85 per cent of ball compared to 81 by their opponents.

Tom Robinson. (Photo by Hannah Peters/Getty Images)

If you can win ball from the tail of the lineout consistently, the advantages in attack are maximised. You get to the midfield much more quickly, and it becomes harder for the defence to manage both sides of the ruck. Their forwards have to run further to reach the openside of the first breakdown, and the line spacings on the short side are wider.

The Force understood that threat from their opponents, winning four consecutive Blues’ throws at the start of the second half. Three of those were directed to the tail:

In all three examples, the two defensive pods are set up towards the middle or back, and the Blues lose three prime attacking positions to steals by Sitaleki Timani and Jeremy Thrush. That gave the Force a foothold in the game that they had previously lacked.

They took their lessons from the previous round against the Crusaders, where they had given up the space on or beyond the 15-metre line much too easily for comfort, and made the necessary adjustment in order to compete effectively:

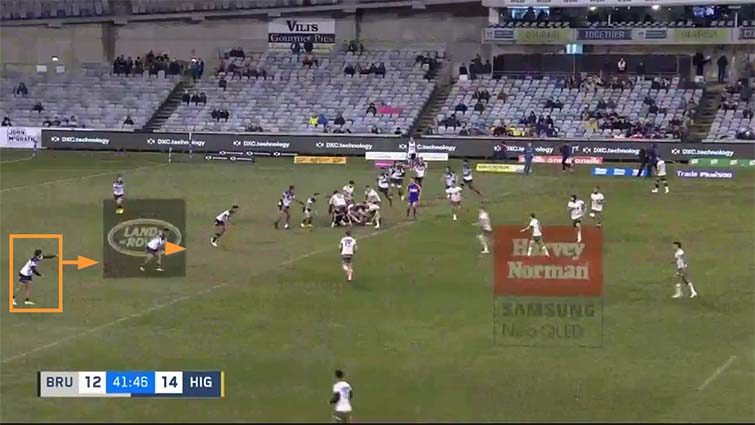

The Force proceeded to score two tries of their own from back ball just for good measure, and move within touching distance of the Blues:

By way of contrast, the match between the Brumbies and the Highlanders was an object lesson in what happens when you give a team from New Zealand a free pass to lineout ball from the tail.

The Highlanders started with a try from a lineout drive off barely contested back ball:

New Zealand hookers tend to be the premier throwers on the planet to the tail and beyond, and they hardly ever underthrow the receiver. If they make a mistake, they ensure it is too long rather than too short. As the above examples show, the worst outcome for the defence is for the jump to go up too far in front of the receiver and give the Kiwis a free play around the end of the line.

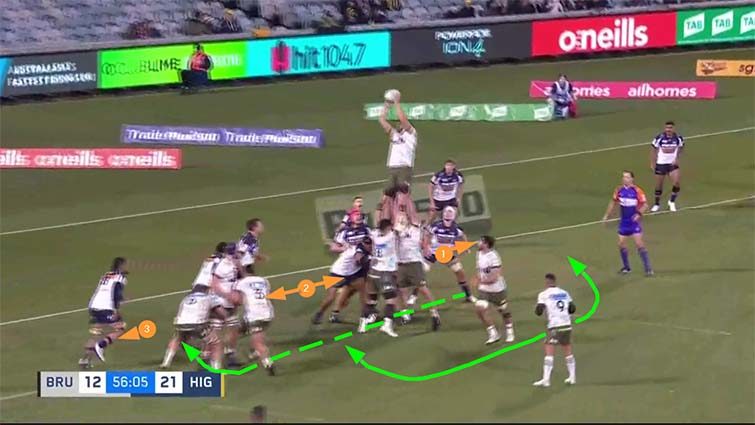

Throughout the game, Highlanders hooker Ash Dixon demonstrated that he belongs in that elite group of throwers:

The dead-straight ball travels more than 20 metres in the air. One simple pass later, the Highlanders are on the edge of the Brumbies’ 22, with the home forwards struggling to reach their defensive positions at the first ruck:

Only two, Rory Scott and Rob Valetini, have managed to wrap because of the depth of the breakdown, while three of the shortside tight forwards are still struggling to make up ground.

A yawning gap has opened between Len Ikitau and Tom Wright on the Brumbies’ right, and this was a scenario the Highlanders were able to exploit later in the half – even with less space available between the two Brumbies:

The pressure from a stream of back ball only grew in the second half:

The tail-gunner, Scott in the white hat, is defending at the middle of the line as the Brumbies’ pod goes up in the air to no avail, giving Pari Pari Parkinson an easy gallop into midfield off another superb delivery from Dixon:

The rest of the defence begins to compress like a concertina, with Tom Wright already positioned five metres inside the far 15-metre line after just one phase of play. It is hard to recover your width on defence from such a beginning.

More easy back ball courtesy of Bryn Evans, more problems for the Brumbies’ outside defence off an attacking chip by Highlanders flyhalf Mitch Hunt.

When the coup de grace finally arrived, it was only right and natural that it should be delivered off uncontested tail ball:

With the ease of transfer between Dixon and Evans, Evans and Josh Dickson, and Dickson to Billy Harmon, it all looks far too much like a training ground exercise brought to life with minimal interference from ‘the vests’.

But the real question has already been posed by the slick delivery of ball from the back of the line, which has widened the gaps and thinned out the forward defence:

The Highlanders could send Aaron Smith around the end, or through the middle of the line on a ‘teabag’ just as easily, but they eventually opt for Harmon around the front, scoring the try unopposed.

Summary

The Trans-Tasman tournament has illustrated the drawbacks of domestic isolationism in Australia in brutal fashion. All of the Australian teams have found the transition to New Zealand skill levels, changes of tempo, and refereeing perceptions far too much to handle.

Of the five franchises, the Force have responded to the challenge most successfully, particularly given the limited playing resources at Tim Sampson’s disposal. If, by some magical smattering of fairy dust, they could have added the likes of Samu Kerevi and a fit Dane Haylett-Petty to their back-line, they would have finished top of the Australian segment of the table.

Tim Sampson. (Photo by Mark Metcalfe/Getty Images)

They have defended better than anyone else in Australia and played a mature possession-based game with ball in hand. They kept scores close, even with more moderate scoring potential than all of the other four franchises. They understood the strengths of the opposition and tried to put sensible counter-measures in place.

With three July tour games against France to be followed in rapid-fire succession by another three versus the All Blacks in August, Wallabies head coach Dave Rennie will be acutely aware of the need to move beyond domestic back-patting in order to get on even terms with the big boys of the global game.

He will know all about the threats posed by New Zealand teams in particular. The sting in the tail, whether it occurs from the lineout or elsewhere, should not come as a surprise.

As the great Green Bay Packers quarterback Aaron Rodgers put it, “For me, it’s always been about preparation, and the more prepared I can be each week, the less pressure I feel, and the more confident I am. As your confidence grows, it’s only natural that the pressure you feel diminishes.”

Amen to that.

Original source: https://www.theroar.com.au/2021/06/16/why-the-sting-is-in-the-tail-at-lineout-time/

https://therugbystore.com.au/why-the-sting-is-in-the-tail-at-lineout-time/

No comments:

Post a Comment